Exploring the Moa: New Zealand’s Lost Giants

Introduction:

The Moa, belonging to the order Dinornithiformes, were a diverse group of flightless birds native to New Zealand. These remarkable birds ranged in size from small turkey-sized species to the towering giants that stood up to 3.6 meters tall. The Moa family consisted of nine species across six genera, each adapted to different ecological niches across the islands. With their long necks, powerful legs, and varied dietary habits, Moa played a crucial role in New Zealand’s ecosystems. However, by the late 14th century, all Moa species were driven to extinction, primarily due to human hunting and habitat destruction. The Moa’s extinction is a poignant chapter in New Zealand’s natural history, illustrating the profound impact humans can have on native wildlife.

Facts:

| Attribute | Details |

|---|---|

| Order | Dinornithiformes |

| Common Names | Moa |

| Extinction Timeline | Late 14th century |

| Kingdom | Animalia |

| Phylum | Chordata |

| Class | Aves |

| Families | Dinornithidae (true moas), Emeidae (lesser moas) |

| Genera | Dinornis, Emeus, Euryapteryx, Anomalopteryx, Pachyornis, Megalapteryx |

| Species | 9 recognized species |

| Natural History and Origin | Endemic to New Zealand |

| Physical Information | Varied sizes, from 0.5 to 3.6 meters in height |

| Appearance | Long necks, stout bodies, powerful legs |

| Scientist Names | Described by early European settlers and later studied extensively by paleontologists |

| Region | New Zealand |

Appearance:

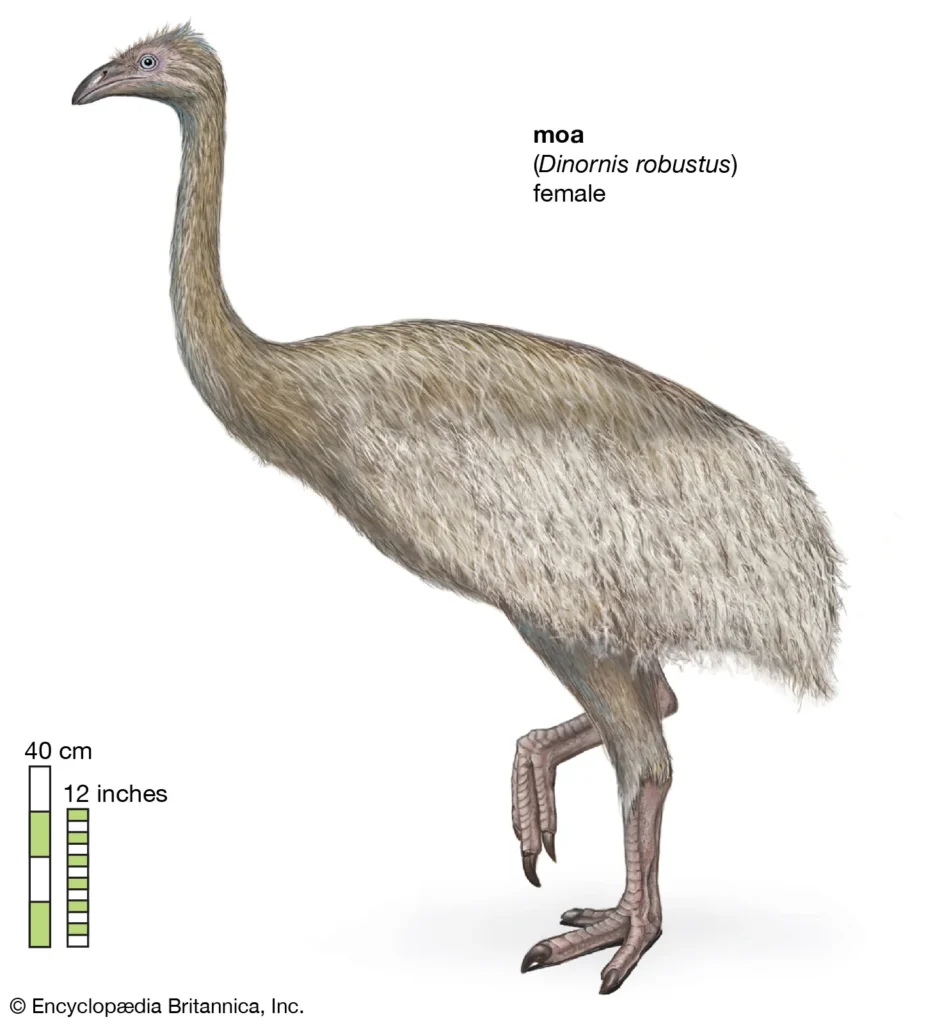

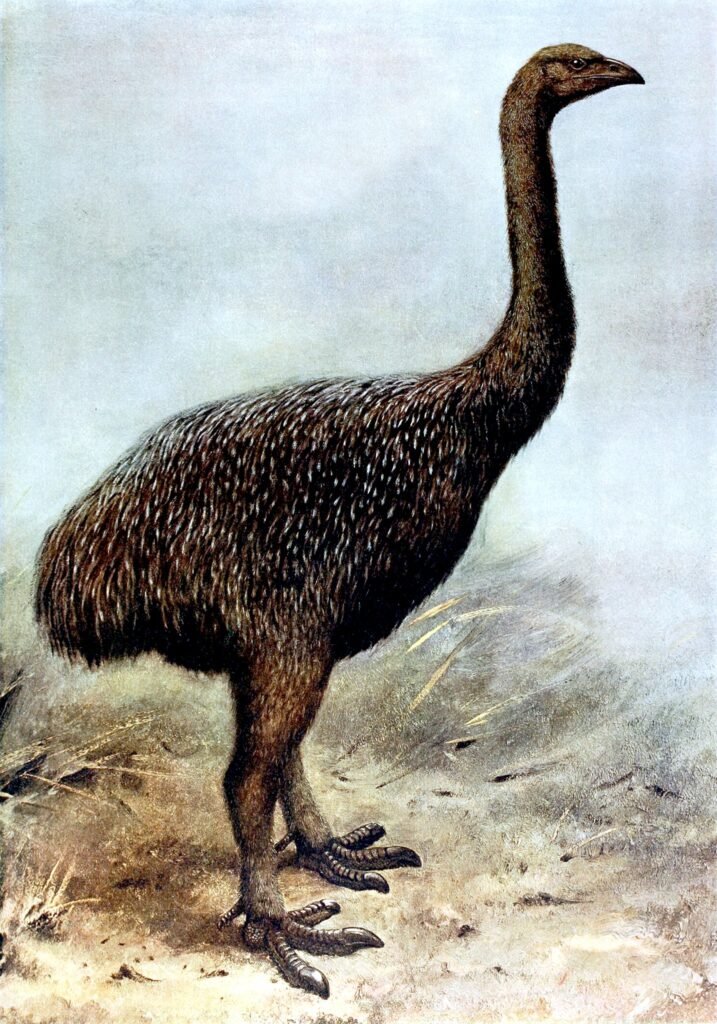

Moas were diverse in size and appearance, ranging from the small turkey-sized species to the enormous giants like Dinornis robustus and Dinornis novaezealandiae, which could reach heights of up to 3.6 meters (12 feet) when their necks were fully extended. Moas had robust bodies, long necks, and powerful legs. Their plumage varied among species, but they generally had coarse feathers that provided insulation. Unlike most birds, Moas lacked wings entirely, having evolved to be completely flightless.

Distribution:

Moas inhabited a range of environments across New Zealand, from coastal forests and shrublands to mountainous regions. Their diverse habitats reflected their ecological versatility, with different species adapted to various niches within these ecosystems.

Habits and Lifestyle:

Moas were primarily herbivores, feeding on a wide variety of plant materials including leaves, twigs, fruits, and seeds. Their diet varied among species, with some adapted to browse on forest understory vegetation and others grazing on grasses and shrubs. Moas played a critical role in their ecosystems, aiding in seed dispersal and shaping the vegetation structure. These birds were likely solitary or lived in small family groups, moving through their habitats in search of food.

Physical Characteristics:

Moas had several distinctive physical characteristics that set them apart from other birds. Their long necks allowed them to reach vegetation at various heights, while their strong, sturdy legs supported their large bodies and facilitated efficient movement through dense vegetation and rough terrain. Moas had a unique skeletal structure with a broad pelvis and robust leg bones, reflecting their adaptation to a flightless lifestyle.

Diet and Nutrition:

As herbivores, Moas had a varied diet that included leaves, twigs, fruits, seeds, and other plant materials. Their feeding habits differed among species, with some browsing on higher vegetation and others grazing on low-lying plants. The Moas’ large size and varied diet allowed them to occupy a range of ecological niches, making them key players in the maintenance of New Zealand’s diverse plant communities.

Behavior:

Moas exhibited behaviors typical of large herbivorous birds, including foraging, nesting, and possibly migratory movements within their habitats. They communicated through vocalizations and body language, particularly during the breeding season. Moas laid large eggs in ground nests, which were likely well-camouflaged to protect against predators.

Cause of Extinction:

The extinction of Moas by the late 14th century was primarily due to overhunting by the Polynesian settlers who arrived in New Zealand around the 13th century. The rapid and extensive hunting, coupled with habitat destruction through deforestation and the introduction of non-native species, led to a swift decline in Moa populations. The loss of these large herbivores had cascading effects on New Zealand’s ecosystems, illustrating the profound impact of human activities on native wildlife.

FAQs:

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What led to the extinction of the Moa? | Overhunting by Polynesian settlers, habitat destruction, and the introduction of non-native species. |

| When did the Moa go extinct? | By the late 14th century. |

| What did the Moa eat? | Moas were herbivores, feeding on leaves, twigs, fruits, and seeds. |

| Why is the Moa significant? | The Moa represents an important part of New Zealand’s natural history and highlights the impact of human activities on large, flightless birds. |

| Are there efforts to study the Moa? | Yes, ongoing paleontological research aims to understand their biology, ecology, and the factors leading to their extinction. |

Keywords:

Moa, Dinornithiformes, extinct megafauna, New Zealand wildlife, human-induced extinction, flightless birds, natural history, ecological impact, prehistoric fauna, species adaptation, environmental changes, paleontological research, herbivorous birds, island ecosystems, wildlife preservation.

Categories:

- Extinct Birds

- New Zealand Wildlife

- Conservation Efforts

- Prehistoric Ecosystems

Views: 20